How Weak Property Rights Contribute to Venezuela’s Crisis

PRA Interviews Aureilio Concheso President of the Advisory Board of Venezuelan think tank Centro de Divulgación del Conocimiento (CEDICE)

By: Philip Thompson

In Venezuela, a political and economic crisis has been unfolding on the world stage. Daily images of street demonstrations dominate headlines about food and medicine shortages, sham elections, threats of U.S. military intervention, and sanctions . This is hard to believe for many that remember Venezuela used to be one of the richest countries on the continent and has some of the largest oil reserves in the world. At one-time Venezuelans enjoyed a per-capita GDP similar to Norway. However, in present day Venezuela 80% of its citizens have lost an average of 19 pounds of body weight due to food scarcity. Some argue Venezuela’s downfall is due primarily to the drop in the world oil price and others attribute it to more functional changes in the legal and judicial system that is part of the former President Hugo Chavez’s “socialism for the twenty-first century.” Property Rights Alliance discussed what role property rights have played in the Venezuelan crisis with Aurelio Concheso the former president of the Venezuelan Center for the Dissemination of Economic Knowledge for Freedom and current president of its advisory board.

Dr. Concheso what is the property rights situation on the ground in Venezuela? Article 112 of the Venezuelan Constitution guarantees ownership of private property, yet we have read many stories about the state seizing companies and private property.

Unfortunately, property rights in Venezuela are basically what the Government wants them to be since Hugo Chavez became president. The erosion did not happen overnight and has been a gradual but relentless process which started with a Constitutional Convention which at least in that case was convened and later approved by popular vote. The first sector targeted was the agricultural sector with a methodology which later was extended to other sectors such as industry and services. In some cases, expropriation processes were initiated and carried out according to the law; in others, outright confiscation with no recourse to the courts, and in others an outright purchase of the property after obscure negotiations. This last method was used particularly during the oil boom years after 2005 where, for a while, money was no object.

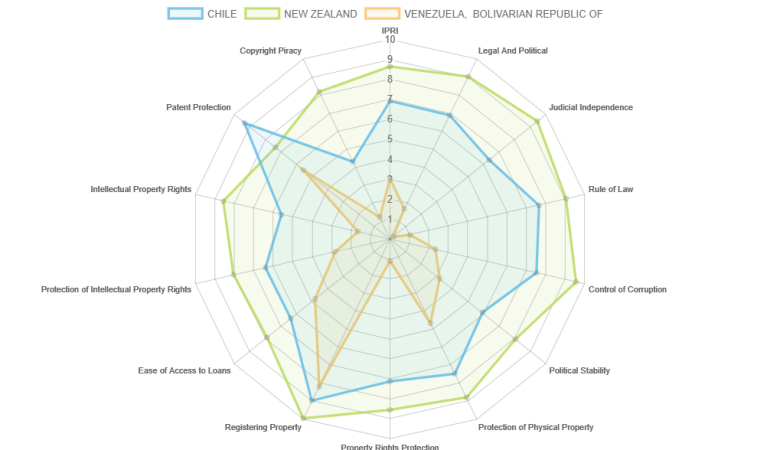

The International Property Rights Index finds that countries with the weakest protections of property rights have their lowest scores in the Legal and Political component of the Index, but this is the opposite for countries with the highest overall property right scores. Have legal and political factors contributed to the loss of property rights in Venezuela?

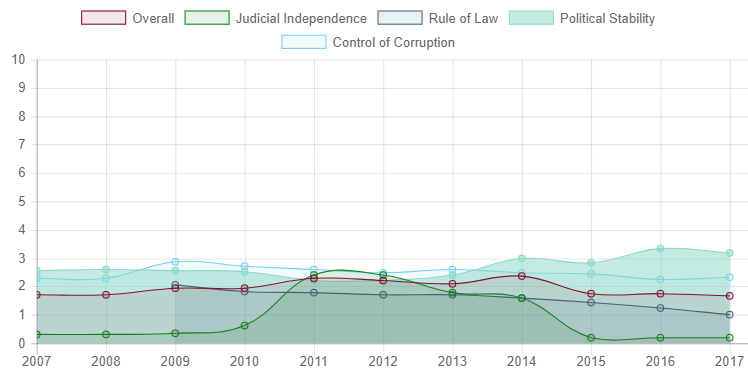

The legal and political environment is the reason for the erosion of property rights. The Chavez Government used to brag that it was a “democratic revolution” with frequent trips to the ballot box. That is until the December 6, 2015 election, the last relatively free election held in the country. The Opposition Coalition MUD won a two thirds majority in the National Assembly. Since then, the erosion has accelerated as the rule of law and the separation of powers has totally disappeared, and the National Assembly was arbitrarily stripped of its power to oversee and control the Executive Branch or name members of the Judicial Branch through constitutional processes. The present Constitutional Court was named in a totally illegal and unconstitutional way by a lame duck Assembly in December of 2015 and is packed not only with government supporters, but with lawyers that do not have the minimum qualifications to be judges, much less Supreme Court Justices.

We are hearing about food shortages, medicine shortages, energy shortages, and about demonstrators clashing in streets with police. Is there a connection between the nationalization of industries and the erosion of property rights with the shortages of food and medicine?

Most definitely so. Agricultural and livestock production has plunged since the Government expropriated or confiscated over 5 million hectares (12.5 million acres) of prime land. The Sidor steel mill that had been privatized in the 90´s and was producing 4.5 million tons a year was renationalized and now barely produces 250 thousand tons. The three main cement companies were nationalized and now produce 50% of previous production. Numerous agri-businesses, edible oil and juice manufacturers, etc. saw production plunge, in many cases to zero after being nationalized … the list goes on and on. In the Oil & Gas sector, many service companies that had been in business for over 50 years were confiscated (because their owners were never compensated). Their businesses became incorporated into the national oil company PDVSA, and only the employees remain on a bloated payroll that has gone from 40,000 workers to 140,000 most of which work doing political activism and not operating rigs or refineries. The same applies for a large number of hotels that were the backbone of an incipient tourism industry, and a pharmaceutical and medical supplies industry which has been reduced to less than 25% of its former self.

Can you tell me more about that – why, once owned by the government, did they suddenly produce less?

Maybe It’s different in other parts of the world, but in Venezuela when the government confiscates, expropriates, or does a friendly takeover of a producing company several things happen at once and accountability goes out the window. The newly appointed managers have a pressing need to acquire new company vehicles, preferably Cadillac Escalade SUV´s with chauffeurs and bodyguards; close and not so close relatives, political activists, plus an undetermined number of girlfriends and/or boyfriends fatten the payroll. Actually producing goods, much less doing it at previous levels, goes way down on the list of priorities.

All this is facilitated by the government’s covering the widening deficit in cashflow with generous subsidies from taxes and oil royalties, and, when these dry up, by the convenient recourse to unchecked printing of money. It finally dawns on the managers that the less they produce the more they can import as finished goods of their respective product line. This is a very “smart” decision, since by having access to the preferred currency rate they can over invoice the finished product and not only measly portions of imported inputs. The Andean Development Corporation estimates that 40% of government imports have been over invoiced since exchange controls were established in 2003, an unheard of percentage in similar situations in other countries.

Some companies take longer than others to deteriorate but the result is always the same. To give an extreme example, a company that produced refractory bricks for the lining of steel mill ovens, stopped producing 6 months after takeover. All the workers are still there sitting around playing dominoes and the bricks are now imported from India at a hefty overprice. The bright side is that fewer over invoiced bricks are needed because the steel mills production has plummeted 95% (from 4 million tons to 200 thousand) after being renationalized.

Normally the type of shortages and hunger that now exists in Venezuela is associated with fourth world countries with poor sanitation, electrification and industrial infrastructure. At the advent of chavismo, Venezuela was a middle-income country with a sophisticated infrastructure base bulit over the post WW2 period. Industrially, just as an example, the now practically defunct automobile components industry exported, among other things, Cadillac components to Detroit assembly lines. Now all of this is in tatters, we are not talking here about a poor country that needs to start from scratch, but rather a country that is in a postwar period without ever having been at war, other than the one its government unleashed on the country by virtue of obliterating property rights and the Rule of Law. In the meantime the government has created unimaginable arbitrage opportunities for those in power, in particular, with two controlled exchange rates at Bs 10/$ and Bs2,900/$ while the black market or free exchange rate at which ordinary citizens can access hard currency is Bs,10,000/$.

CEDICE was mentioned in a recent The Intercept report. As former president of CEDICE would you like to respond to the story?

We have worked with the Atlas foundation for many years and I know Alex Chafuen very well. Knowing him, I very much doubt that Alex would work with the US government, especially in the last 8 years, under any circumstances.

It always amazes me that there are people within the US democratic system that seem to feel that somehow cooperation with the US government would be a bad thing, but being in the payroll of dictatorships such as Cuba, or the one the Chavez government has established in Venezuela, to finance projects such as the Sao Paulo Forum and the Podemos Party in Spain is somehow a good thing.

During my tenure in CEDICE we carried out a project called “Proyecto País” presenting a governance proposal that we hoped the Chavez Government would participate in. There was no hidden agenda, the numerous seminars that formed part of the project were public and government officials participated enthusiastically in them. That is, until spurred by Ms. Goelinger´s distorted use of the U.S. FOIA Chavez decided to pull the plug on said participation as part of his plan to radicalize the march to a collectivist society